Category Archives: EMSL Projects

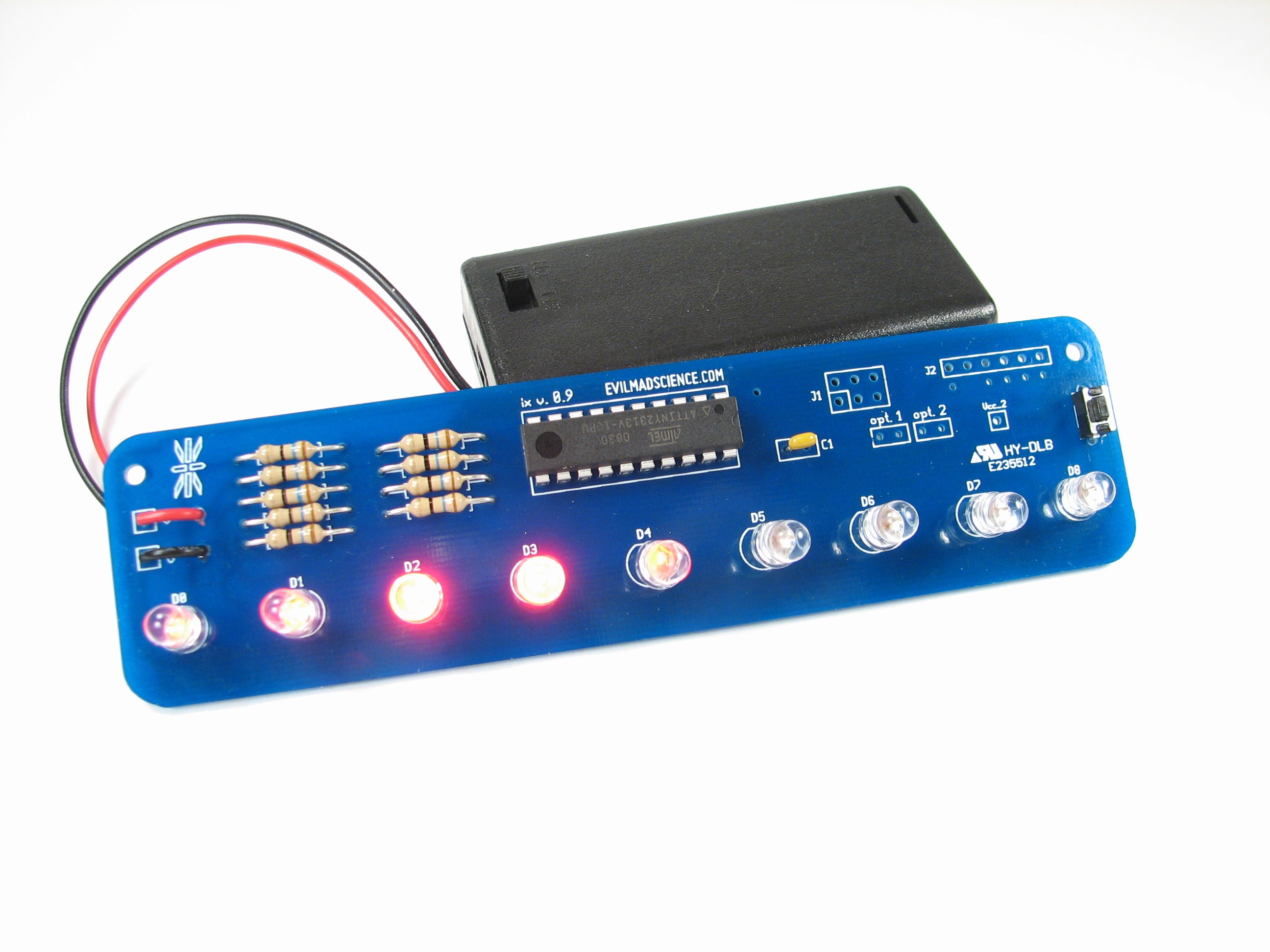

A new Kraftwerk-inspired LED tie kit?

Well, almost— With a breath of new firmware, our Larson Scanner kit takes us on a trip to the late 1970’s.

In the old videos of electronic music pioneers Kraftwerk performing their classic The Robots, a prominent prop is the animated LED necktie worn by each member of the band. If you haven’t seen this, or it’s been a while, you can see it right here at YouTube. (Additional viewing, if you’re so inclined: Die Roboter, the German version.)

The Kraftwerk tie has nine red LEDs in a vertical row, and one lights up after the one above it in a simple descending pattern. And what does it say to the world? One thing only, loud and clear: “We are the robots.” Now, if you’re anything like us, the most important question going through your head at this point is something along the lines of “why am I not wearing a tie like that right now?”

The good news is that it’s actually easy to make one. And the starting point? A circuit with nine red LEDs and just the right spacing: our open-source Larson Scanner kit. With minor modifications– a software change and dumping the heavy 2xAA battery pack–it makes a pretty awesome tie. In what follows, we’ll show you how to build your own, complete with video.

Microwave Oven Diagnostics with Indian Snack Food

Microwave ovens are curious beasts. A super convenient method of warming up certain foods, for boiling a cup of water, melting a little butter, or reheating frozen leftovers. But all too often, those frozen leftovers end up scorching in places and rock-hard frozen in others. Is this just random? Is it really the case that microwaves cook the food from the inside out or left to right or back to front? Well, no, but the way that microwaves work can be mighty counter-intuitive.

Our own microwave oven is definitely one of those that likes to produce scalding yet frozen output. That isn’t necessarily such a big deal if you have patience to reposition a dish several dozen times in the course of a five minute warm up. But we recently (and quite unintentionally) came across a situation– while cooking, of all things –where the radiation pattern became clear as day.

As we have written about, we enjoy roasting papadums (a type of Indian cracker) on the stovetop. Appalams are a closely related cracker made with rice flour in addition to the usual lentil flour that can be cooked in the same ways, but just happen to be significantly more flammable.

So, while you can (with great care and a nearby fire extinguisher) roast appalams on the stovetop, we decided to try out the microwave method. We put several of the appalams on a plate. They start out as plasticky brittle wafers like you see above.

And then, after 30 seconds in the microwave, here is what we saw:

Holy crap!

As an area of the cracker cooks, it bubbles up in just a few seconds, leaving clear marks as to where there is microwave power and where there isn’t. For this particular microwave, Saturn-shaped objects will cook evenly.

Obviously what is happening is that there are two hotspots in this microwave: one in the center, and one offset from center which traces out a circle thanks to the rotating plate in the bottom.

We have access to four other microwave ovens. Are they all this bad? Continue reading Microwave Oven Diagnostics with Indian Snack Food

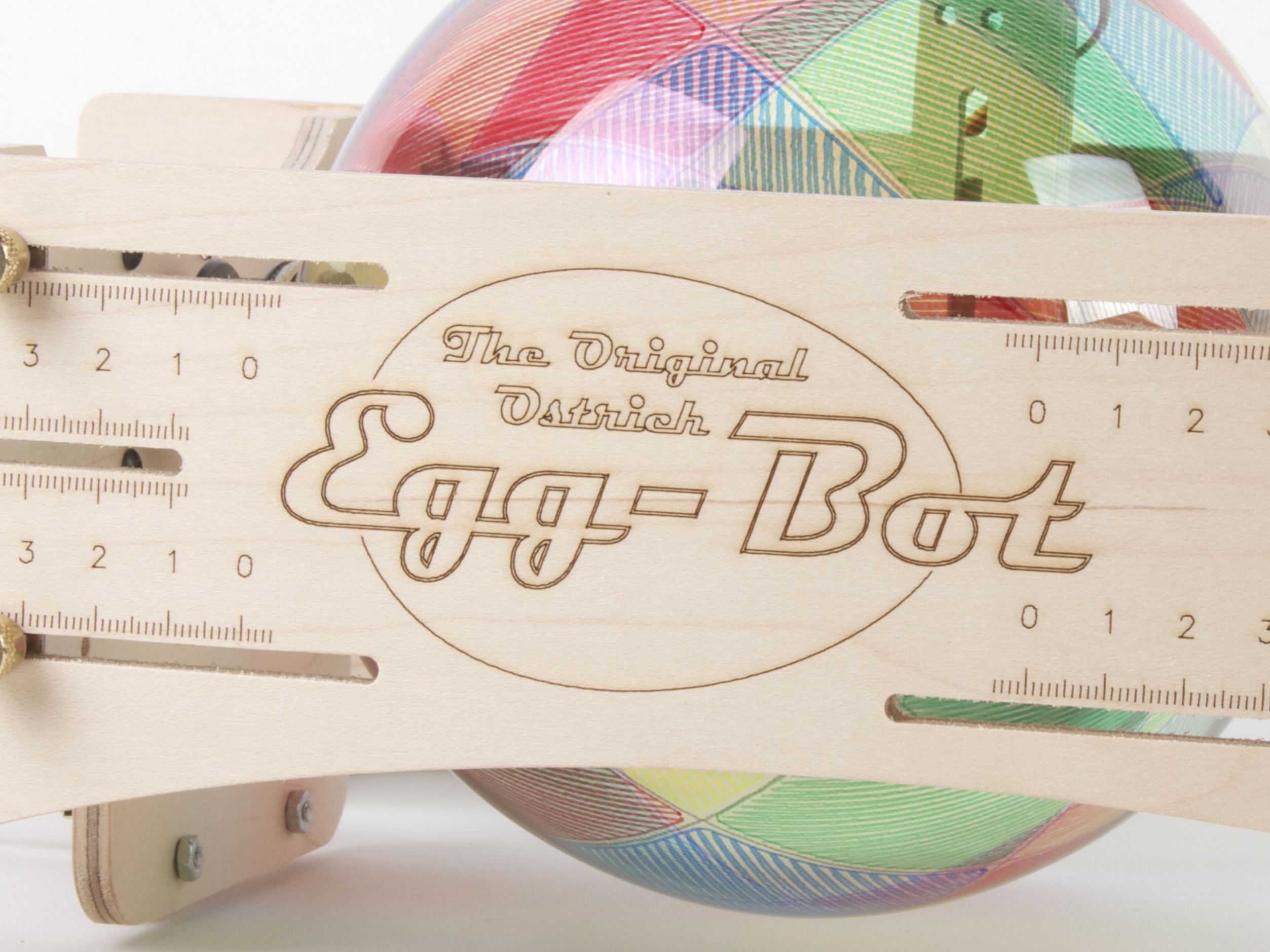

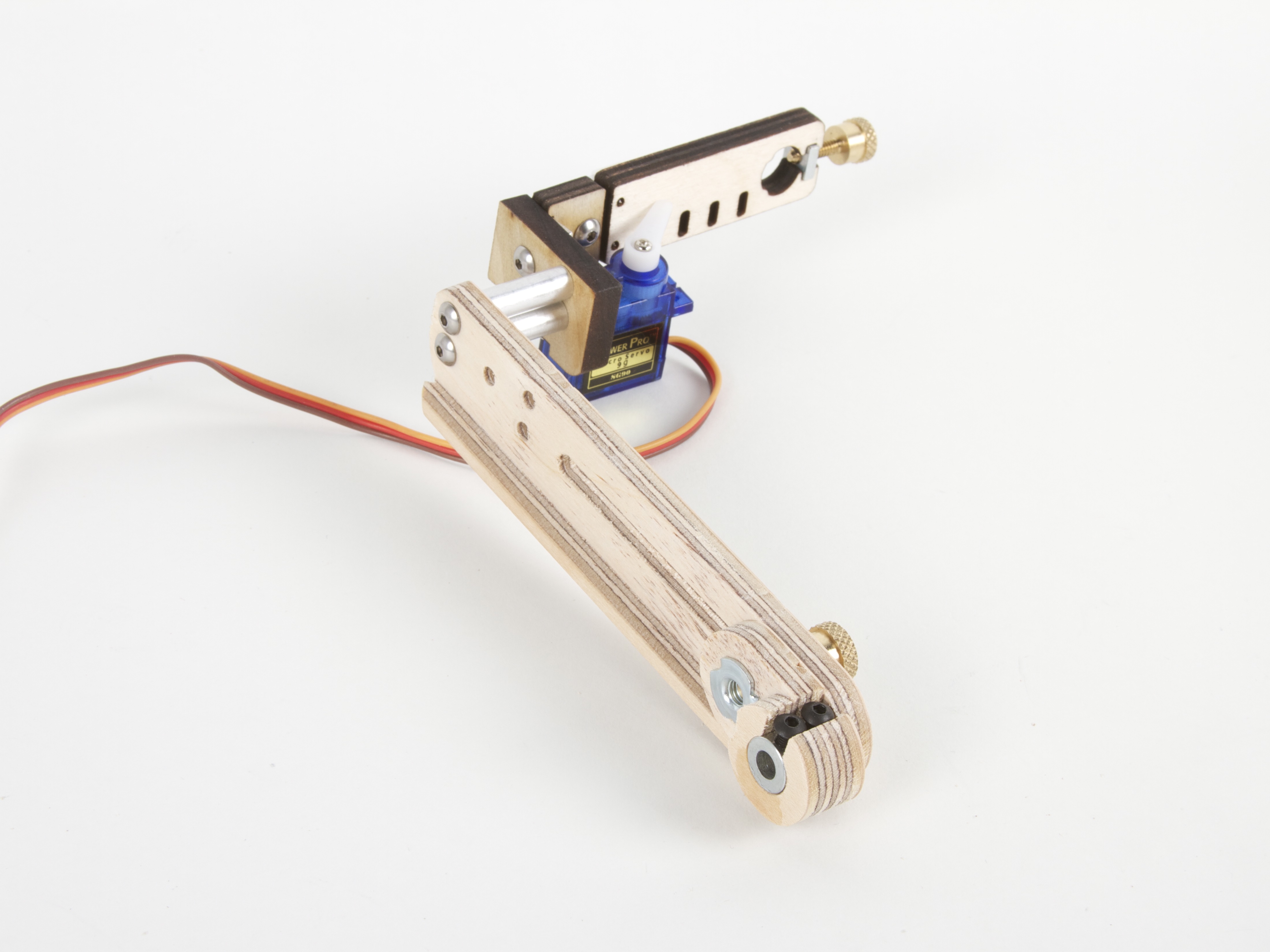

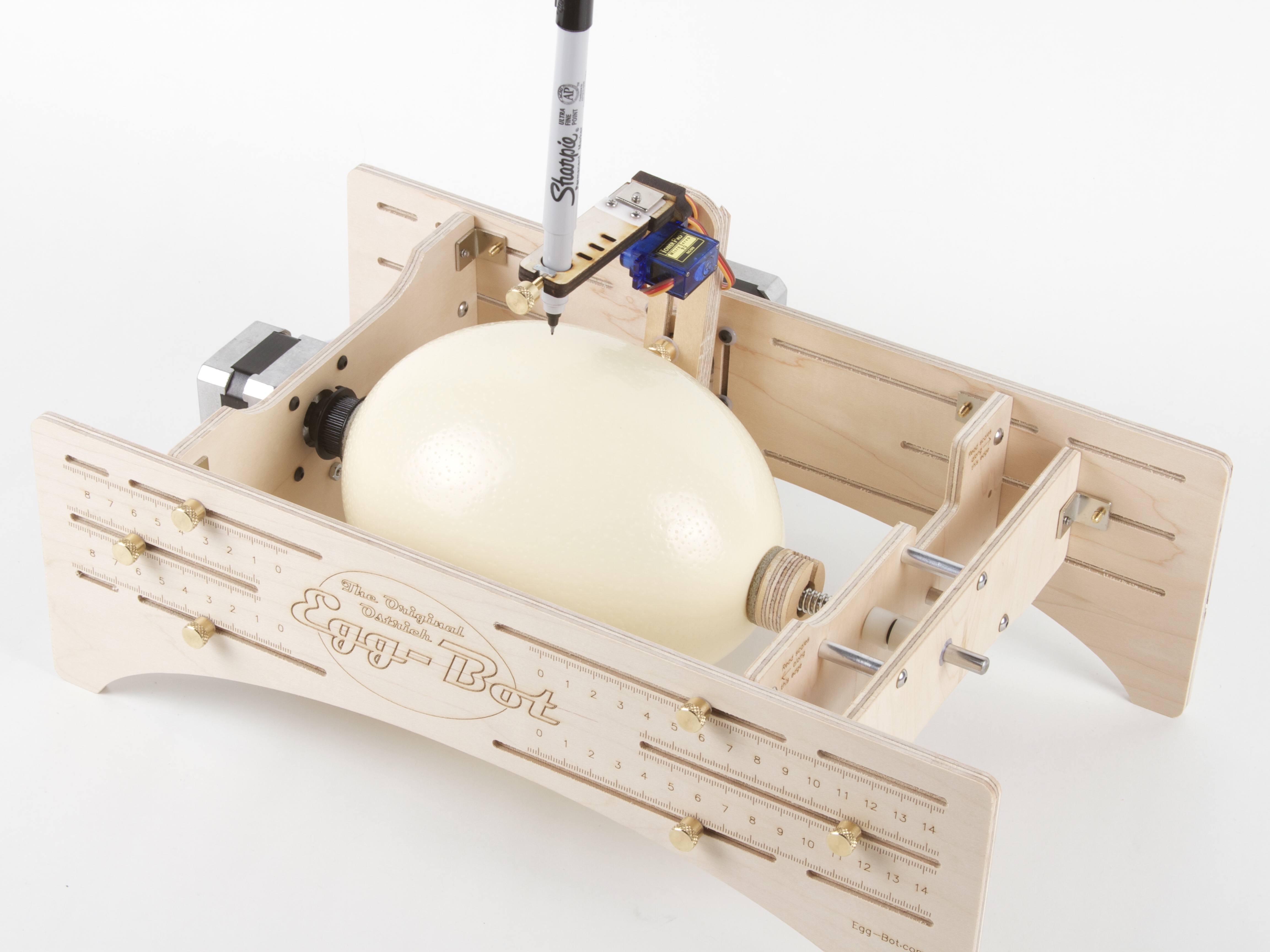

Eggbot at MadCamp

Pete over at RasterWeb! recently posted that he’s planning an Eggbot session at MadCamp. MadCamp is a BarCamp – an open-format conference where the attendees are the presenters — in Madision, Wisconsin on Saturday, August 27. If you’re near Madison and interested in learning more about the Eggbot, unconferences, or any of the other topics that will be presented, go check it out!

We’ve featured Pete’s work with the Eggbot before in our roundup of Eggbot art, and we’re thrilled to see him sharing his mad Eggbot skilz. He invites MadCamp attendees to bring files to print on the Eggbot, and his post provides a nice brief primer on what it takes to get designs sharpie-ready.Photo by Pete Prodoehl released under cc by-nc-sa license. Egg Egg design also by Pete Prodoehl and released to the public domain.

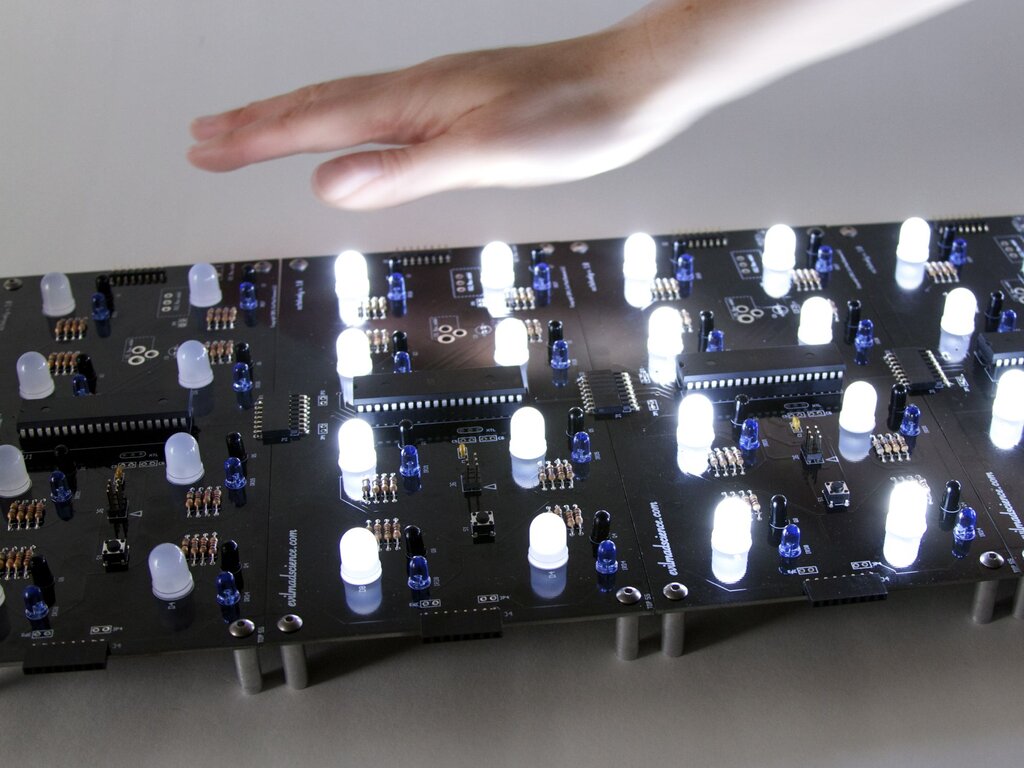

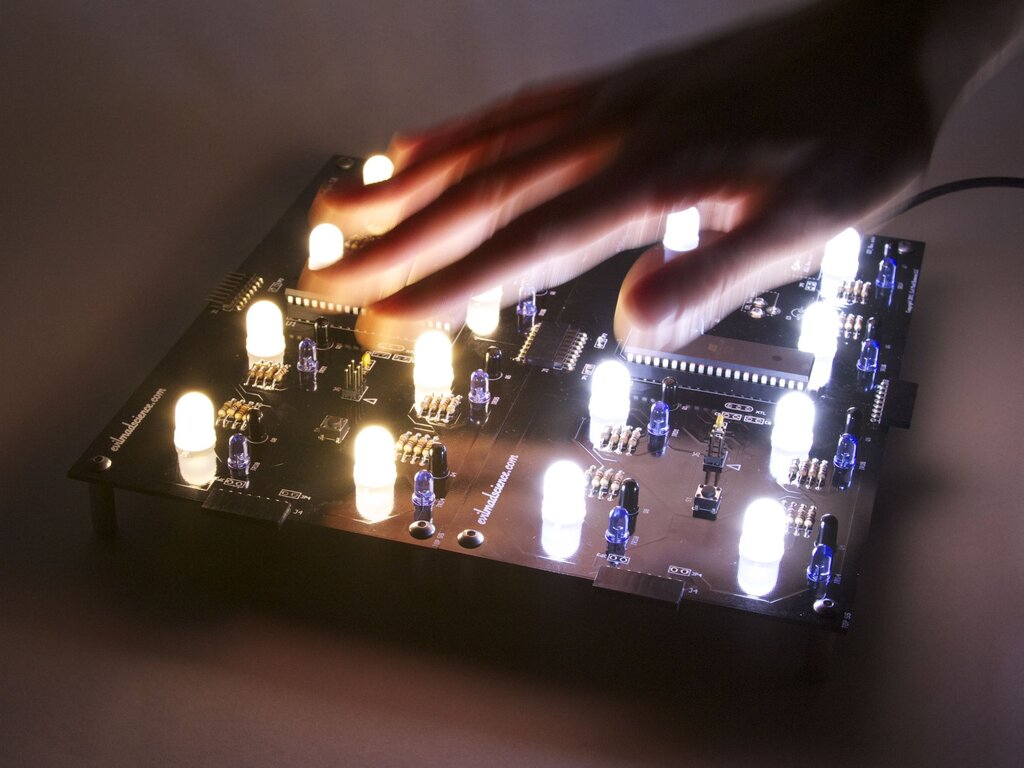

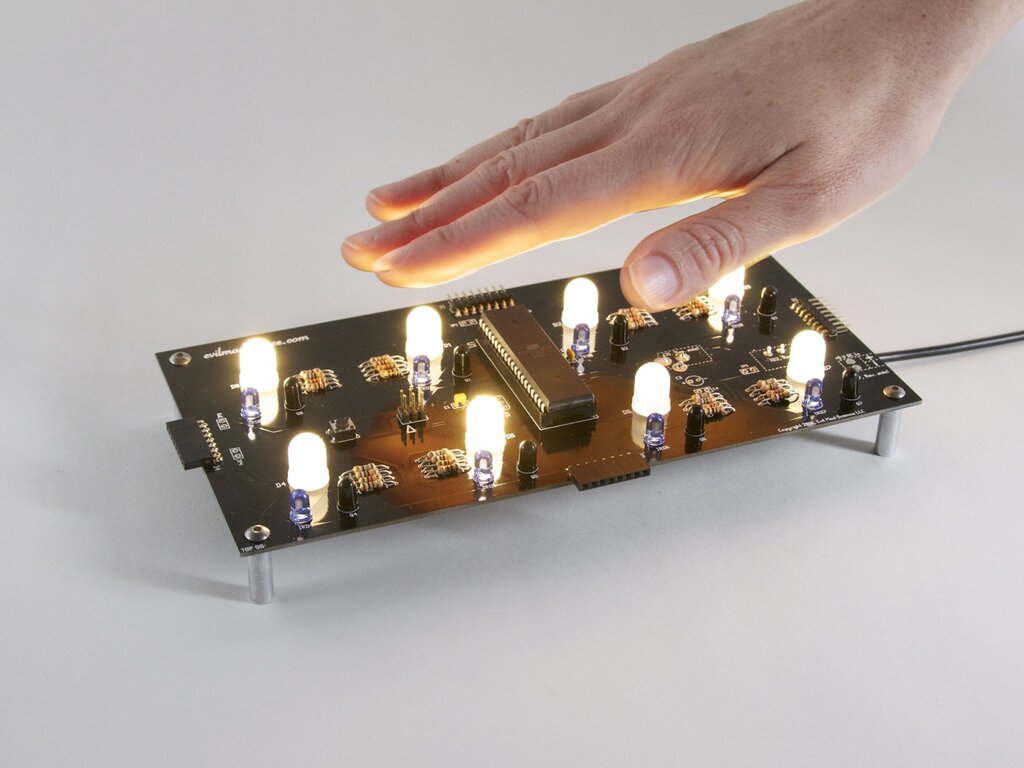

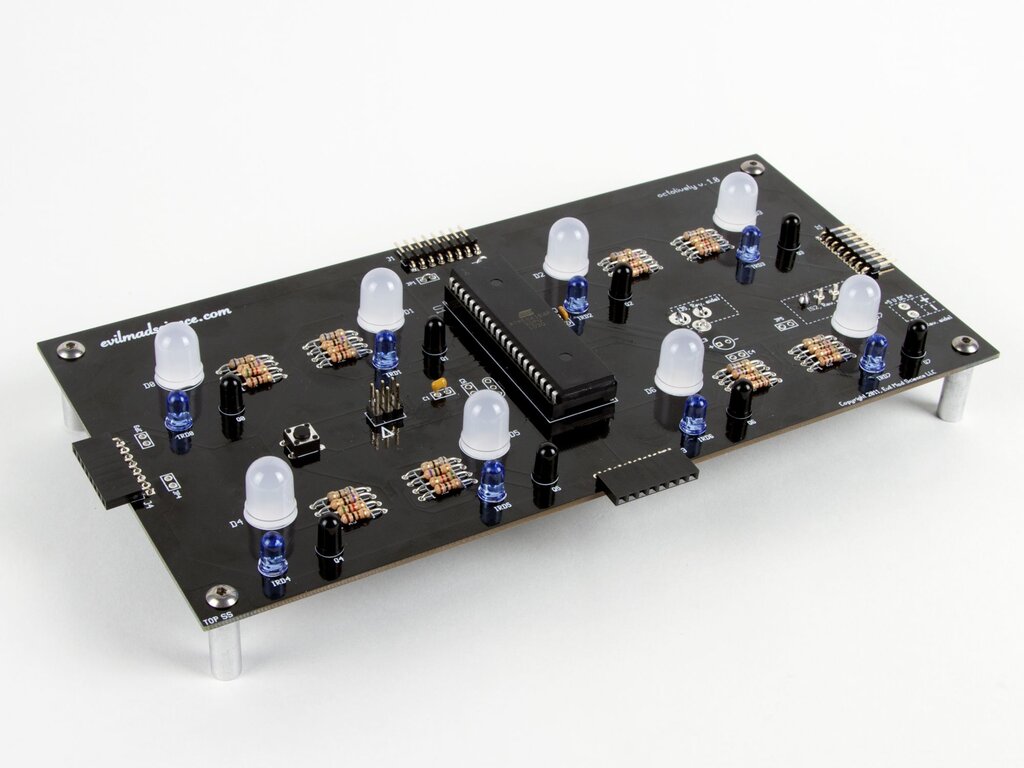

Octolively: Digital interactive LED surfaces

Octolively is an all-new, open source interactive LED surface kit that we’re releasing today. Octolively features high resolution– an independent motion sensor for every LED, stand-alone operation, a variety of response functions, and easy scaling for large grids.

Octolively represents our fourth generation of interactive LED surfaces.

Long-time readers might recall the original Interactive LED Dining Table, the infamous Interactive LED Coffee Tables, or the third-generation, not-very-creatively-named Interactive LED Panels. All of these surfaces were based on fully-analog circuitry with large circuit boards and a fairly high ratio of LEDs to sensors– typically 20:1.

Octolively, by contrast, is based on smaller, lower-cost circuit board modules, “only” 4×8 inches in size. Part of the reason for this is so that there’s more flexibility in making arbitrarily shaped arrays. Arrays can now be as skinny as 4″ wide, or as wide as you like.

Each module features 8 LEDs and 8 independent proximity sensors– one for each and every LED. The LEDs are (huge) 10 mm types, and that chip in the middle of the board is an (also huge) ATmega164 microcontroller.

Octolively, by contrast, is based on smaller, lower-cost circuit board modules, “only” 4×8 inches in size. Part of the reason for this is so that there’s more flexibility in making arbitrarily shaped arrays. Arrays can now be as skinny as 4″ wide, or as wide as you like.

Each module features 8 LEDs and 8 independent proximity sensors– one for each and every LED. The LEDs are (huge) 10 mm types, and that chip in the middle of the board is an (also huge) ATmega164 microcontroller.Each sensor consists of an infrared LED and phototransistor pair, which– together with polling and readout from the microcontroller –acts as reflective motion sensor. The LEDs are spaced on a 2-inch grid, and the edge connectors allow boards to be tiled seamlessly. Because the circuit is now primarily digital, it’s easy to store a variety of response functions in the microcontroller. Our standard firmware contains 8 different response functions– fades, ripples, shadows and sparkles, which you can change with a button press. As it’s an open source project, we’ll expect that (in time), others will become available as well. And, because the entire circuit is self-contained on the module, the surface scales effortlessly– you get very high resolution over huge areas without bandwidth bottlenecks, and no need for a central computer. Of course, static pictures don’t do much justice for interactive LED surfaces. (We’ve embedded our video above. If you can’t see it here, click through to YouTube.) And doesn’t that look good with warm white LEDs? Octolively begins shipping next week. Additional details– including the datasheet and documentation links –are available on the product page.

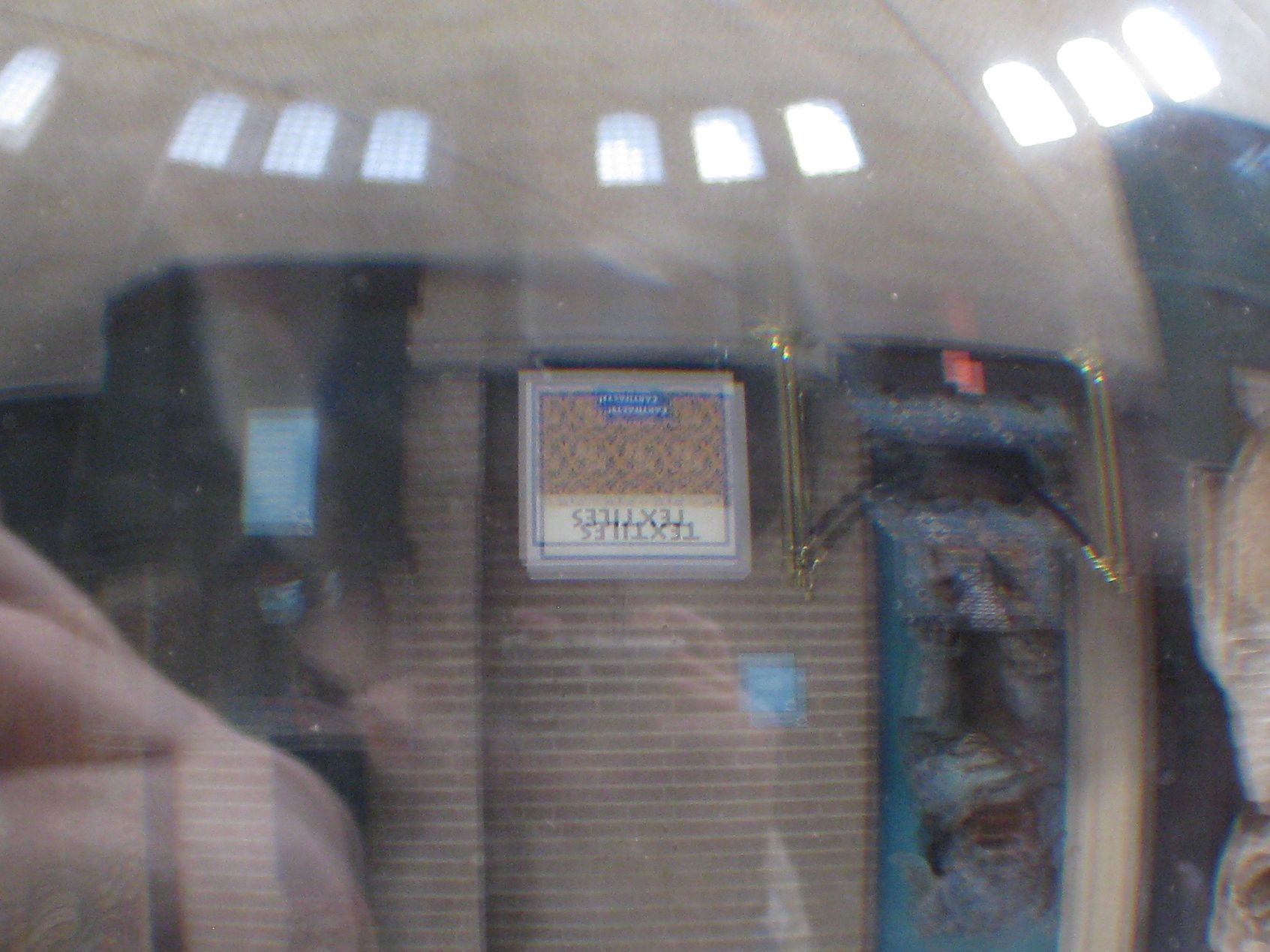

A stunning display of natural birefringence

For a higher-quality image– without the display case– take a look here.

Here is what the display placard has to say:

For a higher-quality image– without the display case– take a look here.

Here is what the display placard has to say:

“Crystal Sphere

Rock crystal, Silver Stand

Qing Dynasty (1644-1911 CE)

China

An ornamental treasure of the Imperial palace in Beijing, the crystal sphere was said to have been a favorite possession of the Empress Dowager Cixi (1836 -1908 CE), under whose watch imperial China crumbled. The rock crystal originated in Burma and was shaped into a sphere though years of constant rotation in a semi-cylindrical container filled with emery, garnet powder, and water. The forty-nine pound flawless crystal sphere is believed to be the second largest in the world. The stand in the shape of a wave was designed by a Japanese artisan.”

So, not only is it a giant crystal ball, but it’s a historically interesting giant crystal ball. But besides that– and its brief modern stint as a hat rack –what’s genuinely remarkable about this particular artifact is that it’s made from a chunk of rock crystal, better known as quartz crystal. Now, those “crystal balls” that run-of-the-mill fortune tellers use are often just glass— glorified playground marbles or perhaps so-called lead crystal, which is actually just another type of glass. Quartz crystal, on the other hand, has a structured atomic lattice that leads to some very interesting physical properties including piezoelectricity, triboluminescence, and birefringence. These properties arise from the crystal structure itself; they are typically minimal or absent in glasses such as fused silica (glass made by melting quartz crystal). While the museum probably wouldn’t want you compressing or grinding their crystal ball for piezoelectricity or triboluminescence experiments, the birefringence is boldly sitting out on display. Let’s look a little closer: The sign, across the room reading “TEXTILES” is not just inverted like it would be with a spherical lens, but also– plain as day –appears as double image, even through our single camera lens.

Why? Quartz crystal is a birefringent material, which means that light rays entering the material experience two different indices of refraction, depending on their polarization and orientation with respect to the crystal lattice. In practice, our eyes see all polarizations, so this means that the crystal ball acts like a superposition of two glass balls with different indices of refraction– and light rays entering the sphere at any given point can follow two different paths to reach your eyes. Hence the double image.

It’s also worth noting that the two separate images are composed of photons with perpendicular polarization. If you were to look at this sphere through a linear polarizer (e.g., one lens of the 3D glasses that they use in modern movie theaters), you could turn it such that only one of the two images was visible at a time.

The sign, across the room reading “TEXTILES” is not just inverted like it would be with a spherical lens, but also– plain as day –appears as double image, even through our single camera lens.

Why? Quartz crystal is a birefringent material, which means that light rays entering the material experience two different indices of refraction, depending on their polarization and orientation with respect to the crystal lattice. In practice, our eyes see all polarizations, so this means that the crystal ball acts like a superposition of two glass balls with different indices of refraction– and light rays entering the sphere at any given point can follow two different paths to reach your eyes. Hence the double image.

It’s also worth noting that the two separate images are composed of photons with perpendicular polarization. If you were to look at this sphere through a linear polarizer (e.g., one lens of the 3D glasses that they use in modern movie theaters), you could turn it such that only one of the two images was visible at a time.

Birefringence is not particularly rare, and there are materials (like certain forms of calcite) that have huge, easily visible birefringence. Optical devices made from flawless natural calcite, exploiting this property, are tremendously important to scientific research and industry.

We tend to think of a quartz crystal as being perfectly clear– not something that gives you a double image when you look through it. That’s because quartz is only very weakly birefringent, especially when compared to calcite. Quartz is, however, still extensively used in industry in applications for which high transparency and very slight birefringence are key, such as optical wave plates. And, what’s truly remarkable about the Penn Museum sphere is that this tiny property– usually so hard to see –is so plainly visible to the human eye. Finally, as we mentioned, the amount of birefringence depends on the orientation of light rays with respect to the crystal itself.

This means that if we walk one quarter circle around the sphere to a point where we’re closer to looking directly along (or perhaps, perpendicular to) the optical axis of the quartz sphere, the image suddenly becomes (if you’ll pardon the pun) crystal clear.

Finally, as we mentioned, the amount of birefringence depends on the orientation of light rays with respect to the crystal itself.

This means that if we walk one quarter circle around the sphere to a point where we’re closer to looking directly along (or perhaps, perpendicular to) the optical axis of the quartz sphere, the image suddenly becomes (if you’ll pardon the pun) crystal clear.

Magnetic Googly Eyes: For the Benefit of All Mankind

Make repositionable googly eyes with sticky-backed rubber magnets, or promotional magnets and a drop of glue.

Continue reading Magnetic Googly Eyes: For the Benefit of All Mankind

The HP Xpander

Behold, in all its glory, the “HP Xpander.”

Not just a relic from the age of brightly-colored transparent plastic, but what could have been the future of HP graphing calculators. Continue reading The HP Xpander

555 Footstool

The succinct story of a modest little footstool– involving datasheets, cnc routing, laser engraving, plywood, glue, chips, all-thread, angle grinders, mountains of sawdust, dowel rods, spray paint, and a picture of a cat.

Does this LED sound funny to you?

At first glance, these might appear to be normal 5 mm (“T-1 3/4”) clear lens ultrabright yellow LEDs. However, they’re actually “candle flicker” LEDs— self-flickering LEDs with a built-in flicker circuit that emulates the seemingly-random behavior of a candle flame.

In the close-up photo above, you can actually make out the glowing LED die on the left side, and a corresponding-but-not-glowing block on the right: the flicker circuit itself. In what follows, we’ll take a much closer look, and even use that little flicker chip to drive larger circuitry. Continue reading Does this LED sound funny to you?